My previous visit, in 2008, was rather short, but did begin the

effort to have Arthur and Paula Schmidt, who hid us for almost 2 years on their

fruit orchard in Worin, officially recognized and dedicated as Righteous

Among the Nations, and to have my mother, Lina Banda Weber, registered

as a victim of the Holocaust. Filling

out the initial forms was a somewhat perfunctory task and carried little

emotion.

This trip, by contrast, was charged with feeling, both sad and

joyous, and still lingers in my mind. An added benefit this time was that Rusty

was fully recovered from his infection and was able to join us, making it a

complete family experience.

Our hotel, in the old part of the city, was small and charming,

and could have come right out of the Tales of the Arabian Nights. Mosaic tiled floors, middle eastern

lanterns, Moroccan-style arched windows

and shutters, claw-footed bathtubs with European fittings, Persian rugs, a mix

of colonial and Eastern furniture, indoor and outdoor dining, and various

beautiful gardens made our stay both memorable and comfortable, even though I

had to have the shower door removed and that lovely old fashioned bathtub

shoved over a bit so I could get in the bathroom!

I left word for grandson Arthur Schmidt, his wife Julia and son Arthur

at their hotel, and soon they joined us for a delicious dinner at our

hotel. It was the first time we met Julia

and young Arthur, age 10, who was very polite but probably very bored with all

the goings on.

Jerusalem, as you surely know, is very, very old, extremely

multi-cultural, and tremendously crowded.

We walked all over the city the next day rubbing elbows with Hasidic Jewish

girls on their way home from school, Muslim shop owners in front of their

restaurants and stores, and Christian tourists making their way to holy sites,

all in a jumble of different dialects, smells, and laughter.

On Tuesday, while others did their own thing, I visited the Power

of Balance (POB) integrated dance company at the Vertigo Eco Art Village,

situated at Kibbutz Halamed, about 40 km outside Jerusalem. After a delicious lunch out in the fields I

watched Hai Cohen and Tali Wertheim, directors of POB, lead about 12 students

through a contact improv session before conducting my own workshop with

them. It was a delight to work with

them. The shared experience of disability transcends any language, stranger or

technical barrier. POB is an offshoot of

the prestigious Vertigo Dance Company, of which Tali was a former member. My afternoon with this wonderful group

eventually led to a collaboration titled “Community”,

which was performed at the annual dance concert CounterBalance in Chicago

in September, 2018.

And on to Yad Vashem the following day, for what turned out to be

a most moving and powerful experience for all of us. For me, it brought back shreds of memory,

tears of sadness that left me at a loss for words, but also comfort in knowing

that I was part of remembering and honoring the couple who shielded my siblings

and me, at the risk of their own lives.

Yad Vashem is Israel’s official memorial to the victims of the

Holocaust, much like the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. It is dedicated to preserving the memory of

the dead; honoring Jews who fought against their Nazi oppressors, and Gentiles

who selflessly aided Jews in need.

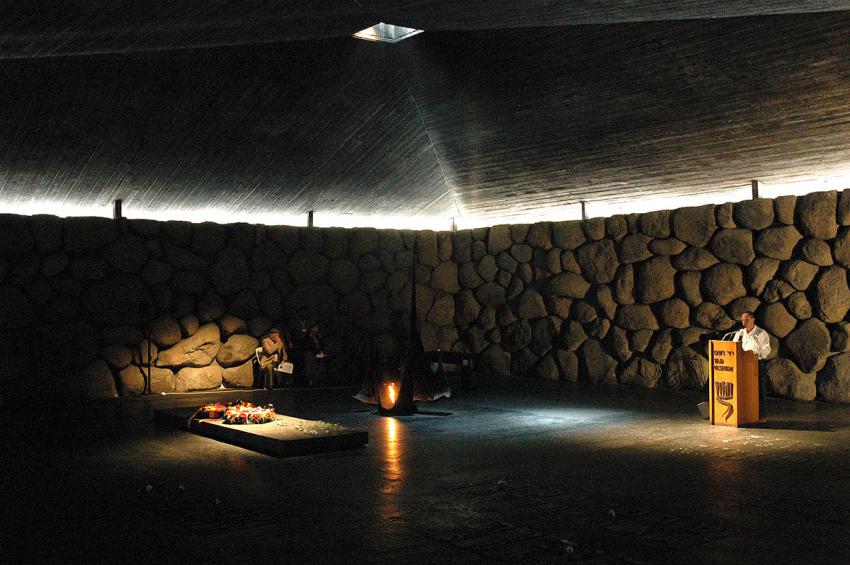

We

first gathered in the Hall of Remembrance, a solemn, imposing structure with an

angular roof that gives it a tent-like shape. There are no seats in this vast, square

space, in the center of which rests a base on which sits the Eternal Flame that

continuously illuminates the Hall.

Before it stands a stone crypt containing the ashes of Holocaust

victims, brought to Israel from the extermination camps. Engraved on the mosaic floor are the names of

22 of the most infamous Nazi murder sites, symbolic of the hundreds of

extermination and concentration camps, transit camps and killing sites

throughout Europe. When I say solemn and

moving, this is what I mean. This Hall of Remembrance is the premier site for

memorial services. The director of Yad Vashem, flanked by Arthur Schmidt’s

grandson, the Consul General of Israel, and another official of Yad Vashem read

the story of Arthur and Paula Schmidt and how they saved us 7 Weber children,

first in English and then in Hebrew, as we and many members of the press looked

on from above. In memory of the victims

of Nazi brutality inside this hall no German is ever spoken.

To conclude this portion of

the ceremony Arthur was asked to approach the Eternal Flame to re-kindle and

re-dedicate it. As the Schmidts’ heir he

was then given a specially minted medal and a certificate of honor bearing his

grandparents’ names, as they were recognized and their names commemorated on

the Mount of Remembrance as Righteous Among the Nations, the official title

awarded by Yad Vashem on behalf of the State of Israel and the Jewish people to

non-Jews who risked their lives to save Jews during the Holocaust. As we exited the Hall I was immediately

surrounded by the press, asking for my impressions, feelings and thoughts. I began to speak but stopped, overcome by

this most moving ceremony, the historic nature and weight of what I had lived

through, and finally the opportunity to say, “Thank you”. The reason for so much press attention was

due primarily to 2 things: first, that all 7 children of the Weber family were

rescued, and second, that a representative of both the rescuers and a

representative of the rescued were present for this dedication. It apparently it is quite rare for a member of

the rescuer family to be found and acknowledged.

We then proceed on a long walk

through the Avenue of the Righteous, where many trees are planted in memory of

rescuers and up a hill to the Garden of the Righteous, where we unveiled the

plaque with the names of Arthur and Paula Schmidt on the Wall of Honor. Before this unveiling, however, another

ceremony was held. This time, outdoors, our group, along with some other

visitors, were seated, with cameras rolling, as the director once again read

our story, followed by remarks by the Consul General, Arthur, and then finally

by me. This time we were not so solemn,

as we were so happy to see the Schmidts’ names, as they rightfully took their

place among the 27,000 names, from 51 countries, that are listed. Of these, only 600 have been recognized as

being from Germany. Many pictures were

taken, Arthur and I gave numerous interviews to numerous reporters from Israel,

Germany, and other European countries who were there, followed by a lovely

reception and refreshments.

The process of having the Schmidts

recognized was begun by me in 2008, but effectively pursued by my brother

Alfons for almost ten years, gathering all the required information. It is an arduous process requiring providing

documentation, possible witnesses, locating relatives, etc. A public Commission, headed by a Supreme

Court Justice of Israel, examines each

case and is responsible for granting the title.

The medal of the Righteous is

inscribed with the Jewish saying: “Whosoever saves a single life, saves an

entire universe”, which is from the Mishnah, one of the Jewish holy books.

No event in life, however, goes

along without stumbles. At the beginning

of our time at Yad Vashem and its’ beautiful paths, and as we began walking up

the hill to the Hall of Remembrance, my chair died! I had trouble charging it the night before,

and the battery decided to give up the ghost there and then. Fortunately I had willing children and even

some strangers push me along throughout our visit until we managed to get to

the wonderful Yad Sarah, a disability center not far from the museum, where a

remarkable occupational therapist provided us with a short term charger and

arranged to have a vendor bring a brand new one to the restaurant we had

repaired to for an evening of food, toasts, and good time.

Subsequent to our trip I

received an email from a journalist in Munich, Germany who had read about the

Yad Vashem ceremony. He asked if he could come here and interview my sisters

and me. He came in May. His article is

included in the Links section of the blog.

It is titled “Buch Zwei” (Book Two)

I was also contacted by a

researcher who lives in the town of Indersdorf, Germany, where we spent several

weeks in a children’s DP camp. My

daughter Beth, a filmmaker, is making a documentary about our story, and will

visit with this person and several others this coming summer.

The story never ends…………

Here are the remarks I gave at the ceremony:

Ceremony Yad Vashem Remarks 14 March 2018

Good afternoon, my name is Ginger Speigel

Lane, nee Bela Weber, the youngest of 7 children born to Alexander and Lina

Weber.

It is with a deep sense of humility and

awe that I stand here to represent my family in honoring Arthur and Paula

Schmidt as Righteous Among the Nations. In the Hall of Remembrance you learned

of their selfless commitment to shelter, and save, our family during the Holocaust,

a horrific period in world history, truly its darkest hour. As the seventh and

youngest of seven – Alfons, Senta, Ruth, Gertrud, Renee, and Judith, I am

honored to speak on their behalf, and to recount a few of their memories and my

own. Memories are very fuzzy after so many years, and a little confused between

time in Worin and time in Berlin. I am only sorry that my brother Alfons, who

worked so diligently to gather all the documents to enable this event is not

here with us; his memory was great, and he would have had quite a few stories

to share.

Because I was so young, age 3-5, the few

memories I have are not very precise. Three states of being stand out for

me: always being cold, always being

hungry, and always feeling alone. I

remember playing outside by myself in a large field, which was either behind or

part of the Schmidt’s fruit orchard where we lived, and digging for

potatoes. Even with some extra ration cards from the mayor of the village,

Rudi Fehrmann, there was never enough food.

We were always hungry! And I would say to my sister Gertrude, who was

like a mother to me, “Ich bin so allein.—“I am so alone!--why am I always so

alone?”

We slept in a separate building from the

main house-the laundry, really-which had bunkbeds-and kept to ourselves. We were

really on our own and had to fend for ourselves as the Schmidts were not around

much, but I remember Herr Schmidt as a kind, rather jovial man. I wasn’t afraid

of him, I liked him. His wife Paula kept

more to herself.

Herr Schmidt picking us up from the

hospital where we were incarcerated, and driving us to the farm at night. We

were scared, and told to keep to ourselves. No one remembers ever walking into

the village; once when Renee and Gertrude went to Berlin to bring food to Papa

and Alfons, they had to take the train back to Worin. They got lost because they went too far. Renee

recounts that strangers took up a little collection to pay for their train fare

back, and told them where to get off near Worin. It was late at night, they

didn’t really know their surroundings but walked several kilometers being

scared 8 and 10 yr olds til they got to the farm.

Herr Schmidt hid us in the potato cellar

when strange men came to the property. Again, we were scared. Actually, we were all pretty scared all the

time, both on the farm and in Berlin. Renee recalls rabbits down there in a cage

Papa had made. The next morning Gertrude went down to see them and they were

all dead. The rabbit story is disputed by Ruth, who said we had rabbits in the

attic in Berlin, not the farm. As I said earlier, memories get confused.

Judith sometimes went to neighbors to ask

for potatoes. There was also another family, a woman and her daughter, who

lived at the farm, but they didn’t stay with us in the laundry shed. They stayed elsewhere. More evidence of the

Schmidts’ kindness.

Ruth was always chopping down little

trees for firewood. In fact, we all collected twigs and branches in the woods

for the fire. That was one of our jobs, along with picking strawberries on the

side of the road, and doffing for potatoes. Ruth remembers washing lots of

clothes in a big tub in the laundry building every day, after which she would

go walking in the woods a lot.

We got back to Berlin just ahead of the Russians-a

week or two before the war ended, and I remember standing in line with a tin

bowl or cup at an outdoor soup kitchen. I also remember standing between Papa’s

legs, sort of hiding behind him, watching German soldiers, and then the

Russians, marching down the street right in front of us.

There was constant street to street

fighting and aerial bombing. Because my father was clever and rigged up a radio,

we got alerts when planes were on their way, giving us time to run to the

bunker in the Alexanderplatz, which was only a couple of blocks away. But we

missed one alert and a bomb hit our building just as we got down to the basement

shelter. It wasn’t really a bunker, just the basement of our apartment building,

and we were separated from the others in the building who went into an actual

bunker. All of us were down there, along with Papa, except for Gertrude, who

was in the hospital with a severely injured leg after having been run over by a

truck. The bomb made a direct hit, tore

off the top of the building, completely blocking us in, unable to dig ourselves

out. At some point Herr Schmidt came and dug us out. Without the Schmidts we would never have made

it out. We really owe our lives to them.

Our overall feeling during those times was

one of moderate fear, not knowing who was a friend, who was not, not knowing

who strangers were. But that was the case

during the entire war. We really didn’t know

anything different. When Arthur Schmidt,

who had been an acquaintance of Papa’s, realized he could not care for the

family once our mother was gone, and stepped forward to help, our fortunes

began to change, and our lives were truly in the hands of the Righteous Among

the Nations.

Endnote:

After the war, and after we left for America, my father remarried. One

day, his stepdaughter, Gitta aged 6-7, was home alone, and there was a knock on

the door. She had been told never to open the door, and so she didn’t. The people knocking were the Schmidts, who

had come to check on Papa. Gitta has

always felt terrible not letting them in, but of course didn’t know who they

were. We did hear from them, however,

and have a wonderful picture of them, which clearly shows what good, kind

people they were.

And here are the remarks I made to young Arthur 3/14/2018:

Young Arthur, don't ever let anyone tell

you that there is only evil in the world. There is good in the world, a million

times more good than evil. You didn't know your grandfather and great-grandfather,

of course, but he lives inside of you. You have a wonderful heritage and legacy,

and should be incredibly proud to carry on his name.

Judaism teaches, in fact, all religions

teach, that there are two paths in life: Good and Evil. You stand on the

threshold of adulthood, and you have before you these two choices—Good, which

leads to righteousness, and Evil, which is only destructive. Arthur, you always have a choice. Choose the

path towards goodness and righteousness. You will be proud of yourself, and you

will honor your great-grandfather and grandmother’s memory as you carry on

their good name.